Finding a path: A look at making cycling safer for kids

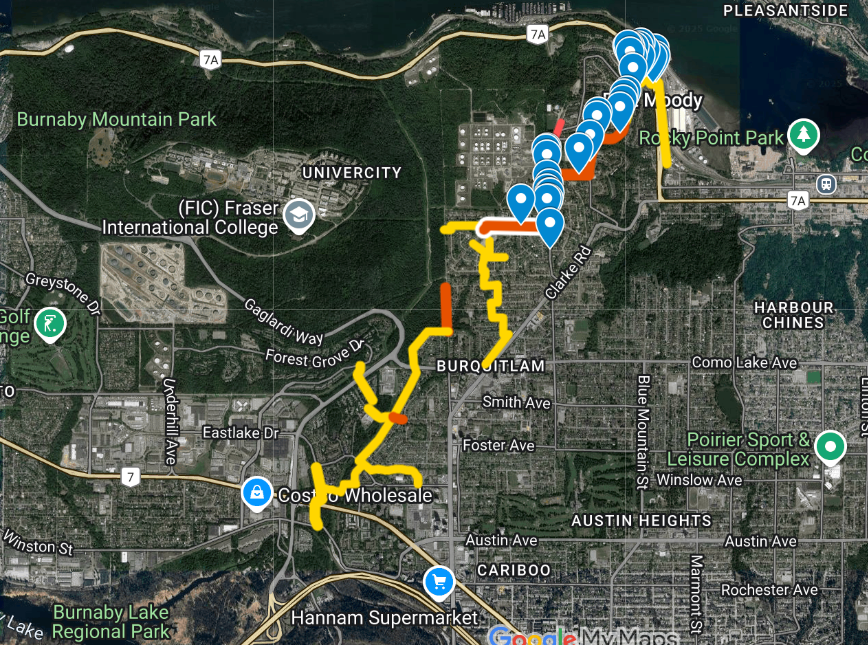

A Port Moody family made a map highlighting their safety concerns biking in their neighbourhood

The Steeves’ family used to commute to their school, Glenayre Elementary, on two wheels.

It got too dangerous.

They would bike along the shared lane Glencoe Drive and have cars try to pass them, sometimes drivers would yell at them to get off the road. Even riding on Glenayre Drive, which has a painted bike path, didn’t feel safe.

Local news that matters to you

No one covers the Tri-Cities like we do. But we need your help to keep our community journalism sustainable.

“It was too dangerous to be on the bike lane because of the painted lines, and we would be squished between the buses and cars and trucks and the cars’ front doors. And if they would open their front doors, we would get smacked,” said Forest Steeves, age seven.

“As a parent, it’s terrifying,” said Brian Steeves. “Riding your bike to school is like installing a playground in the middle of a roundabout.”

Forest and his brother Winter, age nine, both love biking, and the latter wanted to attend a local HUB cycling meeting.

“I wanted better cycling infrastructure,” he said.

There, they learned how to make a map, where they highlighted the cycling gaps in the Glenayre, College Park, and Seaview neighbourhoods.

This map showcases various safety concerns from a kid’s point of view, like the fact there’s no curb drop to access the southbound bike path on Glenayre Drive (it’s challenging for kids to hop the curb), or that a section of Glencoe Drive is too wide (which encourages faster traffic) and too busy during morning drop-off and afternoon pick-up times.

“I made it just so that the people at HUB would kind of know how we feel about our neighborhood — and from the perspective of kids, because as adults, we sometimes forget what it’s like to be a kid and some of the barriers to riding,” Brian said.

For example, he pointed out a law passed by the province last year that legislates drivers must stay at least one metre away from vulnerable users — which includes cyclists.

“But if you’ve got a four year old riding his bike – I think adults have completely forgotten how unpredictable a four year old is,” Brian said. “And on a little bike, a four year old will just see something to the left of them or to the right of them, and just turn.”

Both Winter and Forest say they would rather bike to school than walk, as they currently do. Even at their young ages, its not hills nor distance that deters them. When Winter was six, he biked from Port Moody to the Vancouver Aquarium and back, and both of them have biked to their grandmother’s house in Pitt Meadows.

Brian said he thinks biking is a good opportunity for his kids to develop a sense of independence. But for now, he says it’s simply not safe enough to let them ride on their own.

“If you wanted to consciously stop kids from biking to school —design it the way they have. And the evidence is that you will not find a single kid’s bike at the elementary school,” Brian said.

Making streets safer

There are a number of things cities can do to make streets safer — and encouraging drivers to slow down is a big one.

While Port Moody (and the other Tri-Cities) have made progress developing multi-use bike paths, HUB Cycling, a cycling advocacy group, is now advocating for what they call slow streets, according to Colin Fowler, the co-chair of the HUB Cycling Tri-Cities Local Committee.

The initiative includes narrow streets to encourage drivers to slow down, raised crosswalks that force people to stop at stop signs, and modal filters (where every several blocks there’s an intersection that only allows bikes and pedestrians to move through, and cars have to turn).

It means that that rat run route is no longer as positive of an experience, because you can only travel on it for so many blocks before you’re forced to turn off,” said Fowler.

Modal filters are important on ‘rat run’ streets — a route that’s a detour when main arterial roads get clogged with traffic, said Fowler.

“And as a result, places like schools that are on those quiet side streets are no longer on quiet side streets,” he said.

Brian Steeves said he wants completely separated bike lanes for kids’ safety, which he said in some cases is as simple as painting the lines differently. Instead of the bike line in-between the parked cars and moving traffic, it could be between the parked cars and the sidewalk.

“Literally the park cars would protect you from the moving traffic,” he said.

Port Moody’s plan

Stephen Judd, Port Moody’s Manager of Infrastructure Engineering Services, said they’ve been working with elementary schools in the city to identify the concerns of parents, students and staff.

Port Moody has been working on its Active School Travel Plan, where it found residents had similar concerns to the Steeves’ family and Fowler. People’s top worries included speeding vehicles and drivers not stopping at stop signs.

Currently, Judd said they’re working on the design of a pilot program for a traffic calming pilot to service Meadows Elementary School on Noons Creek Drive, as well as for Aspenwood Elementary School on Panorama Drive, among several other initiatives.

But it can be a challenge to incorporate better bike infrastructure while balancing some of the city’s needs.

For example, Port Moody doesn’t have a large road network. “And so by restricting movement of vehicles, there’s not a lot of alternative routes that the cars can take,” Judd said.

So if roads are blocked off to make them more accessible for biking, it could mean that residents have limited accessibility in driving to their own homes.

Another hindrance is that raised crosswalks can cause issues with water drainage on roads, and it can be expensive to put in the infrastructure needed to avoid floods.

Bike lanes can also mean a loss of parking and less space for other road uses, Judd noted.

‘Compounding spiral’

Fowler said they’ve talked to several schools and are trying to implement ‘bike buses,’ where someone rides a bike on a route to school every morning and picks up local kids to join them.

It started in Portland, Ore., and has sprung up in various places around North America.

And while Fowler said school boards are interested, there is also a problem with finding a route.

“The thing that ends up stopping the project in the tracks is when they start looking at a route for a bike bus, they start realizing there’s not many safe streets in the area.”

Biking and walking rates to school are plummeting not just in Metro Vancouver, but across North America, Fowler said.

“There’s a lot of empty bike racks,” said Fowler. “It’s the safety of even getting there in the first place that drives a lot of concern.”

This means that more parents are driving their kids to school, meaning there’s more vehicles on the road, which makes biking less safe and encourages even more commuters to drive rather than bike or walk.

“This is a compounding spiral that makes it untenable for many people to even consider biking or walking to school.”