Raising an anchor: Omar Sachedina’s journey from a Port Moody bungalow to the national news desk

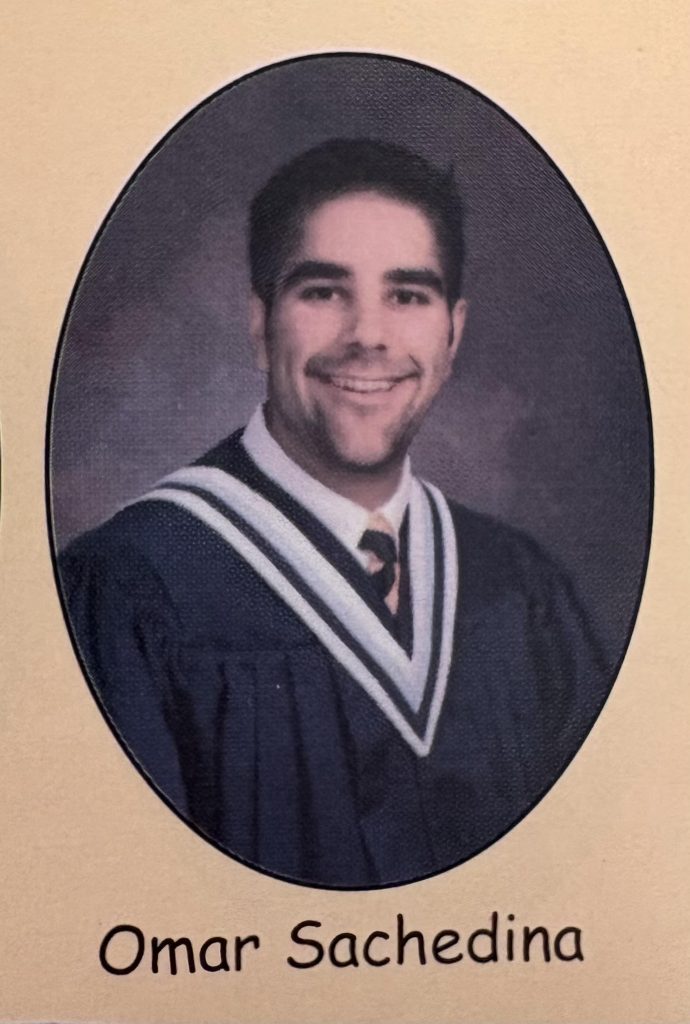

If you were to attempt to draw a line from the 40-something Omar Sachedina on your TV screen four nights a week to a young Omar growing up in Port Moody, you would naturally trace it directly to his Grade 12 yearbook.

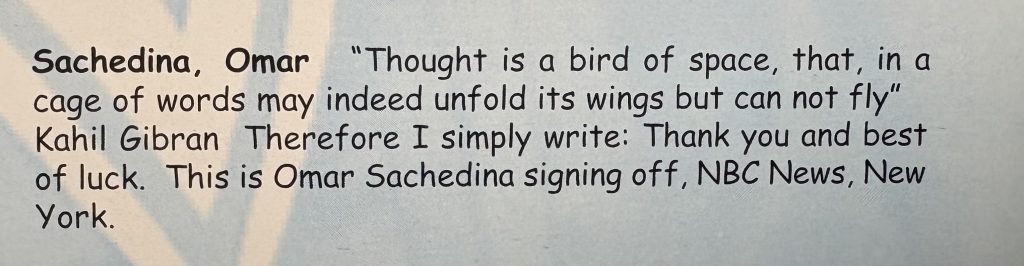

In the Port Moody Secondary School (PMSS) annual for the 1999-2000 school year, on a page dedicated to the class of 2000’s parting words, Sachedina’s are a quote from the Lebanese-American poet and artist Kahlil Gibran followed by a few of his own: “This is Omar Sachedina signing off, NBC News, New York.”

Those words, not so much an act of prescience or even an expression of a 17-year-old’s pie-in-the-sky optimism as they are a declaration of intention and ambition, are an obvious thread between the present of the man who anchors the eponymous CTV National News with Omar Sachedina and his past in the Tri-Cities.

Local news that matters to you

No one covers the Tri-Cities like we do. But we need your help to keep our community journalism sustainable.

But that line doesn’t stretch back far enough.

Because if you talk to his sister or his former teachers or Sachedina himself, this was always going to happen — he was always going to be a journalist; he was always going to work hard, listen harder and do his homework; he was always going to gather and tell stories.

And it started, in part, with a letter to the editor. Remember those?

‘And, so, I wrote a letter to the editor’

“Now, everything’s about tweets and X and social media,” Sachedina says. “But at the time, letters to the editor were a big deal.”

He is speaking via Zoom from his home in Toronto, recounting how a late-1990s study by a university professor that questioned the value of French Immersion education — because, it claimed, students would never reach the proficiency of native French speakers —prompted one of his teachers to write a letter disputing the premise to the Vancouver Sun.

“My teacher wrote a great letter, other parents were wading in,” says the former French Immersion and International Baccalaureate (IB) student. “I saw a major gap, and the gap for me was that there were no students who were writing about this. And, so, I wrote a letter to the editor. . . . So that got me into it.”

That letter, to the Tri-City News, led to another opportunity, to participate in a CBC radio project about the Class of 2000 and the challenges it was facing.

It was hardly a straight shot from that project, however, to broadcasting jobs; rather, Sachedina earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from McGill University, then went on to Columbia University in New York City, where he completed a master’s in journalism before starting his TV career in Timmins, Ont. (he chose not to pursue a job opportunity in Arkansas).

He has since worked as both video journalist and correspondent at the local, national and international levels; covered the war in Ukraine and the 75th anniversary of D-Day in France; travelled the U.S. in the run-up to the most recent presidential election; and reported from an icebreaker in the Northwest Passage.

And even with scholarships and bursaries he earned while going to school, none of it, he notes, would have happened without the support and sacrifices of his parents.

‘He was the type of kid that knew what he wanted’

Nizar and Salma Sachedina were no strangers to sacrifice. Ismaili Muslims whose grandparents emigrated from India to Africa in the 1800s, they were among more than 80,000 Ugandan Asians expelled from Uganda in 1972 by president Idi Amin. Both settled in Vancouver, where they connected and where Salma Sachedina started in the mail room at Vancouver General Hospital and her husband — among the last refugees to leave Uganda — worked in a carpet store.

(In 2022, Sachedina, his sister Nafilia and their mother travelled to Uganda — his mom’s first ever trip back since her family’s expulsion — and filmed a documentary, titled Expelled: My Roots in Uganda. His father had died seven years earlier.)

They raised their family in a home on St. George Street, not far from PMSS, but when he was a tween, got up early to drive him to what was then Maillard Junior Secondary, where he was in French Immersion (in addition to English and French, Sachedina also speaks Gujarati and Kutchi).

Speaking of his parents’ contribution to his schooling even after high school, he says, “There was an absolute commitment to the craft or my life’s work, or what I hoped would my life’s work at that time. And they encouraged me all the way.

“Ultimately, they said, ‘Look, do what your heart says and be the best at it,’” says Sachedina, who, with his wife, Ayeesha Sachedina, recently became a parent for the first time.

“We came from quite humble beginnings and I’m actually deeply indebted to my parents for making the sacrifices that they made.”

Nafilia Sachedina, a social worker in Toronto public schools and a psychotherapist with a private practice there, says she remembers being bundled in the family van for the morning school run and says, “All anyone wanted to do was support him and his goals,” adding, “Omar was just a go-getter and all the while maintaining grace and humility and curiosity. So, watching him motivated me in pursuing my goals.”

She remembers something else, a bulletin board her brother had with 10 goals written on paper and pinned to the cork — “going to this university, travelling to this country, meeting this person” — and says, “He crushed every single goal over the years.

“Omar was like a role model to me growing up,” she says. “He was the type of kid that knew what he wanted and worked hard to get where he’s at. It wasn’t by chance. He was the kid that knew in elementary school and middle school who he was and what he was going to become.”

‘He was always interested in everybody else’

Laurie Saucier remembers that Omar, too. Now retired and living in Victoria, he first taught Sachedina at Maillard, then at PMSS, and says, “He was intrinsically motivated and intellectually curious, and wanted to achieve and do well. Just an ideal student. But as such, he stood apart from a lot of the other kids. . . . He went his own way and I always admired that.”

He recalls returning an essay to Sachedina that wasn’t up to par, with a note on it saying, “You can do better with this.”

Saucier says his former student has never forgotten it.

David Hunnings, who taught in Tri-Cities schools for 30 years before retiring in 2007, says he still talks with Sachedina, whom he remembers from debate class and the long hours he and other debaters spent after school preparing.

“When I think of Omar, I think of somebody who is remarkably intelligent but his intelligence is also tempered by a kind of humanity that, quite frankly, I don’t see much of these days,” Hunnings says. “He was always interested in everybody else. . . . He was patient, willing to hear everybody out first, not always proffering his ideas at the beginning of a discussion about a debate preparation. But he was very good at integrating what he had heard with his own ideas. That’s something that’s quite unusual, especially at that age.”

He adds: “He was very centred, he knew what he wanted, he knew how to go about finding out what he didn’t know, but he also had a great respect for other people in whatever enterprise they were involved in.”

Sachedina says he wasn’t always so self-assured but in remembering his elementary school days — he was “the heavy kid, the Muslim kid” who sang in the school choir and spent more than a few recesses alone — he says those days built in him resilience and strength. He also recalls another teacher, Émilienne Bohémier, who taught him that he had to find his own anchor, and that everything would be OK.

“You need people in life who are encouraging you. . . . And for me, aside from my parents, my friends, my sister and, of course now, my wife, my teachers earlier on were the ones who really showed me about the importance of what really matters in life: treating people with kindness and making sure you do the same to others.”

‘He’s passionate, he’s tenacious, he drives you’

But why journalism?

“I had always loved hearing [different] perspectives. I loved to travel when I could. And I loved meeting and speaking with people. And I loved being able to hear what different sides of a particular issue were.

“There’s a lot about the world that people are always trying to understand,” he says, “and I think you need journalism, you need journalists to be able to contextualize that information and help people absorb not only what is happening but to slow it down a little bit, too.”

Slow is one thing his life is not.

As chief news anchor and senior editor of CTV National News, he may not head to the studio until later but his day starts when he wakes up. He and senior producer Christopher MacInnes-Rae confer early and often, monitoring headlines, crafting story lineups for the national newscasts, writing and interviewing, and editing both copy and video — and pivoting when stories break, an occupational reality.

“We’re trying to give you the context behind the story, not just what happened, but why it happened,” says MacInnes-Rae. “And Omar is really good at distilling that. And if he, you know, reads an intro or a voiceover that you’ve written that’s lacking that, he’s going to call you on it.

“He’s passionate, he’s tenacious, he drives you. We learn to keep up with him . . . because it’s his show, it’s his face on the air and he knows how much it matters.”

“Why does this matter? What’s the context? These are all lessons that I learned early on that still guide the work that I do today,” Sachedina says.

Those lessons started before journalism school, before debate classes. They began in that Port Moody bungalow with a father and young son glued to the evening newscast. Nafilia Sachedina recalls them discussing the stories of the day, and her brother studying and copying the newsreaders’ intonation and delivery.

Sachedina recalls something else.

“I remember I was sort of a weird kid. Even before I went to sleep, I would practise my signoff with different news organizations. So, I was somebody who always lived and breathed it. Call it manifestation, whatever you want, but I really believed in this and it’s something that I was fully immersed in.”

He adds: “I’m a huge believer in the power of visualization, and [this work] is something that I have always wanted to do. The corollary to that is, you never believe that it will actually happen. So did I imagine it? Yes. Did I know that it was going to materialize? I hoped with every fibre in my being that it would, but I didn’t know for sure that it would.”